PITTSBURGH —

Americans love to cleave to cultural traditions that have stood the test of time — especially ones that tell stories of the people who formed their communities, stories that reflect the craftsmanship, sacrifice and hard work of those who came before us.

When inventor and master tinkerer Joshua Lionel Cowen designed an electric fan operated by dry cells — and then, using the same motor that drove the fan, built a miniature railroad car — he began a business and a movement that has enthralled millions of people young and old. Hobbyists not only bought trains and track, but also often created elaborate homemade displays enjoyed by family and friends over the Christmas holidays.

One of the people Cowen inspired was Charles Bowdish, a young World War I veteran and cabinetmaker who lived in Brookville, Pa. He made his first miniature display at Christmas 1919, and to his surprise and delight, 400 people showed up at his home to see it.

Word quickly spread of the Bowdish display beyond Jefferson County, and the young artisan decided early on to keep track of the visitors to his home. In 1953 — the year before he moved his display to the Buhl Planetarium — the family counted 314,874 visitors from every state and 41 foreign countries over 34 years.

It was a tradition Bowdish continued into the 1980s at the Buhl Planetarium, where the line to enter often wrapped around the iconic North Side. Each year, Bowdish spent months painstakingly expanding the display and crafting new scenes that celebrated the lives and livelihoods of Western Pennsylvanians and our industrial, cultural and agricultural impact on the country and the world from the 1880s to the 1930s.

Today, that tradition is in the capable hands of 29-year-old Nikki Wilhelm, who until a few years ago had never picked up a tiny paint brush — or been to half the places depicted in the Miniature Railroad display at the Carnegie Science Center, where most of the Bowdish materials were relocated in the 1990s.

Ms. Wilhelm, a Lancaster native, is the manager of the Miniature Railroad & Village. She has embraced the craft and the history and the storytelling in the same way Bowdish did 100 years ago.

Ms. Wilhelm explains that she started working at the Carnegie Science Center as a part-time program presenter: “It was an entry level, part-time job. I was in grad school at Duquesne studying public history, and I had no background with model trains or modeling or anything like that.”

Her boss at the time, curator Patty Everly who had been with the Carnegie Science Center for three decades, taught her everything she knows, beginning with miniature modeling. Her first piece was the interior of the iconic Strip District Primanti Brothers restaurant.

It was a craft Ms. Wilhelm admits came naturally to her, to her surprise.

Her office is located right outside the 83-foot-long, 30-foot-wide O-scale railroad exhibit. Walking inside is an astonishing step into the past, where the magic of Bowdish’s Jefferson County basement lives on 103 years later, as she often uses common household items to recreate history for the exhibit.

Ms. Wilhelm picks up a red covered bridge from a shelf and turns it upside down. “I’ll show you something cool that Charlie Bowdish built. You see this bridge? Well, it was made from a Milk-Bone box,” she said, pointing to the label from the dog bone company inside the bridge.

“You really just have to let your imagination run wild because you wouldn’t believe the things you can use to make something: the row houses that we have from the Liverpool streets in Manchester, the intricate detail work on the porches — that’s just made from angel hair pasta,” she explained. “The trees are made from dried wild, hydrangea flowers.”

Ms. Wilhelm’s desk is filled with historical documents for research, a magnifying light, branches from the hydrangea bushes used to make the trees every year — all surrounded by three walls of shelves filled with people, homes, buildings, street lights, trains and paint for a craft that requires year-round care.

The popularity of model railroading has stood the test of time in part because hobbyists each bring a different skill set to the craft, which in turn helps develop others: Artisans love building the model scenery; history buffs enjoy researching and recreating places long gone; engineering types enjoy designing the tracks; and techies love the technological advances in electronics, wiring and the ability to run your train from an app on your smart phone.

Ms. Wilhelm says the models for the exhibit are selected by the leadership team at the Science Center. “We always try to pick something that’s historically, culturally or architecturally significant to not just Pittsburgh but the region. We have scenes from as far north as Brookville. We have Titusville and the Drake oil well, and of course Altoona,” she said.

“We try to diversify it; it’s easy to get stuff with city buildings because there’s so much exciting stuff going on in the city, but we try to branch out — like when we did Cement City a few years ago, that was from Donora,” she said.

What she loves most about the exhibit is watching the expressions on people’s faces, especially older people who appreciate the research required to capture a scene accurately. “One thing that’s really helpful is that our staff, basically everyone was a history major, so we put a lot of effort into making sure everything looks as it did,” she said.

One of her favorite creations was the Kaufmann’s Department store windows. “I just looked up old window display photos in the newspaper archives,” she said of her inspiration to get it perfect.

“Once you’ve worked with the miniature railroad for a while, you kind of get the vibe of the exhibit itself. I mean, many people have worked on it over the years, but it still really has kept its integrity. It looks just like it did when Charlie Bowdish was working on it. So we try to use all those same techniques that have been around since he started it over 100 years ago. Everything that Patty Everly has taught me, I now teach the new people. So we just keep the tradition going,” she said.

Royce Beacom is one of the 17 volunteers available for curious children, parents and grandparents to explain each display and detail to visitors. At home, he says, he does modeling for himself and for his grandchildren: “I have five grandsons between the ages of three and ten who love the train; I am trying to pass that tradition on.”

It’s easy to worry the next generation won’t be interested in carrying forward the baton of tradition — the stories and crafts and ideas that bridge the past, present and future of the places we call home. Ms. Wilhelm is a great example of someone who embodies that spirit, carrying forward a magical tradition that began with a kid from Brookville over 100 years ago.

When Bowdish was asked, in one of his final interviews before passing in 1988, why he continued the exacting, painstaking work year after year, he said: “Everyone regardless of their status in life, reaches out towards life’s ultimate achievement — happiness … privileges, money and possessions are useless unless they make a man happy. To those who have been bored and sickened by the monotony of work in offices, sales, fields and factories, where the only evidence of a day’s work is a headache, nothing to exhibit to friends, nothing to view with pride as an example of skill or handiwork — to those people I say ‘You should have a hobby.’”

Forty years later, Ms. Wilhelm’s answer was pretty similar: “When you have a hobby, any hobby, whatever it may be, you need to have the love and passion to really bring that extra spark, the extra ingredient to bring that fulfillment. When you have that, that is a happiness you earn and that is the most meaningful kind.”

![]()

Courtesy of The Pitcher Inn

Courtesy of The Pitcher Inn

Photos by Angus Bremmer, Courtesy of The Three Chimneys

Photos by Angus Bremmer, Courtesy of The Three Chimneys

Photo Credit: Chris Pouget and Anthony Redpath, Courtesy of Wickaninnish Inn

Photo Credit: Chris Pouget and Anthony Redpath, Courtesy of Wickaninnish Inn

Courtesy of Jumping Rocks

Courtesy of Jumping Rocks

Courtesy of Les Trompeurs

Courtesy of Les Trompeurs

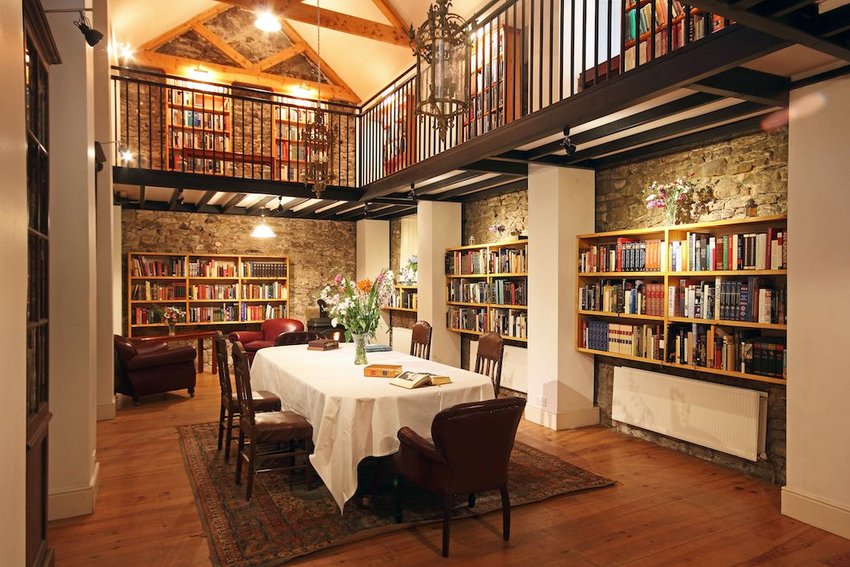

Courtesy of Roundwood Country House

Courtesy of Roundwood Country House

We have a new addition. Meet Yoder.

We have a new addition. Meet Yoder.

We also had Easter decorations.

We also had Easter decorations.