Views: 16

Happy Easter 2025.

Another year where we celebrate another holiday. For many a holy one. On this day you may post religious comments and pictures.

![]()

Views: 16

Happy Easter 2025.

Another year where we celebrate another holiday. For many a holy one. On this day you may post religious comments and pictures.

![]()

Views: 25

Valentines Day with Pictures.

It’s our yearly Valentines Day Pictures. We have a few of the decorations. Not much but you can post some if you wish.

Post even a song or two if you wish.

![]()

Views: 44

Amish go high tech.

When you think of the Amish do you think high tech? I never did until I picked up a local magazine in Amish country in Middlefield, Ohio.

Middlefield is located in northeastern Ohio, just west of Mosquito Lake and borders neighboring town Burton. Middlefield is home to 2,710 people and continues to be a major location known for its Amish community. It is well regarded as the fourth largest Amish settlement in America.And they are more modern then you would think. High tech buggies?

Still horse and buggy, but what’s under the hood. How about heated seats. A dash console with LED components and switches for headlights, taillights and turn signals, all powered by a lithium battery.

And do you think that the horse drawn buggy when needed to stop is the horse doing that all by its self? No my friends they have hydraurlic brakes.

![]()

Views: 32

Holiday decorations at the MC House.

I’m really late this year. Hopefully you enjoy the decorations as much as we enjoy putting them up. But truth be told, my wife and daughter do most of it.

I take the lousy pictures and carry the boxes up from the basement. Oh and I help with putting the ornaments on the tree.

So on this Christmas morning I want to wish all a very Merry Christmas.

You’ll find more pictures in the comments section.

![]()

Views: 66

Pumpkin Fall Works. And other goodies. As usual I’m running late. What’s the old saying? Better late than never? I’m going to add some other photos beside the house decorations. Enjoy.

Scenery from our window seat at an Amish Restaurant in Walnutcreek,Ohio.And Groceries we bought from the Amish in Middlefield,Ohio. The blue bag is insulated for our meat and cheeses.

![]()

Views: 35

Roadwork feels a bit like a necessary evil: Streets need to be in good condition so we can drive safely, but getting stuck in traffic because a stretch of highway is closed for maintenance can be maddening. In Switzerland, engineers have addressed this issue by developing an innovative mobile bridge that enables cars to drive over it while repairs are being done below.

Called the ASTRA Bridge and commissioned by the Swiss Federal Roads Office, the first-of-its-kind structure is about 843 feet long by 25 feet wide, and stands at a little over 15 feet tall. At 1,250 metric tons, it’s a massive beast, but can be set up over one weekend.

“The whole concept had to be designed in such a way that the assembly of the entire bridge on the motorway building site could be carried out in two consecutive nights,” Toni Hauert, head of special vehicles at Marti Technik AG, a construction company involved in the development, said in a statement.

ASTRA is equipped with a remote-controlled hydraulic unit that allows it to be raised 10 centimeters at a time in 328-foot stretches, so workers can repair the highway beneath and then move along to raise the next section. Once put together, the entire modular bridge can be controlled via one device, as all of its 22 power packs are connected to each other.

“This makes it possible to move, steer, and stop this huge unit with just one radio remote control,” said Joachim Kolb, sales manager at Cometto, a transportation manufacturing company that worked on the bridge.

With two lanes and a speed limit of 37 miles per hour, the bridge does create some slowing down of highway traffic, but it prevents the total closure of a highway and the redirection of traffic onto surface streets. Most importantly, though, it increases the safety of workers who’d otherwise be working alongside fast-moving cars.

“The hazard potential for the construction workers involved has been lowered enormously,” stressed Project Manager Jürg Merian, “because the traffic no longer has to drive by them.”

Besides protecting workers from cars zipping by, the bridge provides shelter from rain and sun, making for fewer interruptions due to inclement weather.

It’s currently being employed on Switzerland’s A1, a 254-mile highway that stretches east from Geneva to the village of St. Margrethen near the Austrian border.

Still relatively in its infancy — it was first piloted in 2022 and then tweaked to help improve the flow of traffic over it — the technology isn’t entirely without issues. The Swiss government website contains bulletins about the structure’s status, and multiple report instances of it malfunctioning and requiring repair.

The bridge will hopefully continue to improve, however, and perhaps inspire similar technology in other parts of the world as well. Per Cometto, inquiries have already been fielded from Japan and the Netherlands.

![]()

Views: 28

Just in time for the Holiday. For those who are new here, My wife has different themes that she decorates mostly our kitchen. This is the Patriotic Theme. So enjoy her decoration skills and my lousy picture taking.

![]()

Views: 164

Tuesday is daytrip day to Amish Country. With that comes grocery shopping at the Amish Salvage stores and a stop at a Swiss cheese factory and dinner at Mary Yoders. Below are the groceries we bought two weeks ago. Our Trunk after the first stop.

Forty miles outside of Cleveland, Ohio, Geauga County has been a hub for Amish settlements since the 1880s – boasting the fourth-largest Amish population in the world. It’s also home to some of the rarest genetic diseases in the world.

Now stop number two.

And our trunk after stop number three.

And a stop at Mary Yoders for their stuffed cabbage, bread rolls, and mashed potatoes. for only $9.99. Tuesday special.

![]()

Views: 38

Easter pictures.

I thought that I should show what the before and after pictures look like.

![]()

Views: 19

A Minnesota boy learned his bus driver had cancer. Then he raised $1,000 to help her.

Heidi Carston has spent the past decade bussing children safely to and from school in Minnesota.

That all changed in December when she was diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic gastric cancer. Carston had to tell her students that she wouldn’t see them for a while because of health issues.

One boy just knew he had to help.

“When she announced it on the bus, I was sad,” 11-year-old Noah Webber told USA TODAY on Wednesday. “I was shocked … I didn’t just want to stand there and watch it happen and not do anything.”

After chatting with his family, Noah decided to organize a bake sale in Carston’s honor and ended up raising $1,000 for her.

Noah’s small act of kindness turned out to be a big deal for Carston.

Noah, a sixth-grader at Black Hawk Middle School in the Twin Cities suburb of Eagen, first met Carston at the beginning of the school year.

Months later when Carston realized she would need to undergo chemotherapy and wouldn’t be able to work, she said she just knew she had to tell her students why she wouldn’t be on the bus for a while.

“They’re accustomed to the same driver every day,” she said. “They become accustomed to your habits, your style, and I just didn’t want them wondering ‘What happened to Ms. Heidi?'”

After Noah told his family about what his bus driver was going through, the Webbers baked up a storm, making muffins and banana bread, and then posting about the baked goods on a neighborhood app. Noah’s mom also told her co-workers about it, and another bus driver posted about the sale on an app for bus drivers.

They presented the money and gifts to Carston shortly after Christmas. The gifts included flowers, candy and a blanket.

“I was just blown away,” Carston told USA TODAY on Wednesday. “I just couldn’t even believe it, that he had such a kind heart to be able to even come up with this idea.”

She said she was “overwhelmed by his love and all of the students on all of my routes for giving me gifts … (It was) very, very touching.”

Noah said he was excited and happy to help his bus driver, who he described as kind and “super friendly.”

His father, Mike Webber, said he “couldn’t be more proud” of his son.

The boy’s act of kindness is just further proof that bus drivers are needed and valued, said Allyson Garin, a spokesperson for Rosemount-Apple Valley-Eagan Public Schools.

“They’re these unsung heroes … the first face our kids see in the morning and the last face they see,” she said. “It was just exciting to see the district come together as a whole, including Noah and his fundraiser, with all these amazing things.”

His school principal, Anne Kusch, said his actions embody the school’s philosophy: Calm. Kind. Safe.

“We’re super proud of Noah here and excited to see what else he’s going to do in the next two and a half years that he’s with us,” Kusch said.

Carston said that her diagnosis came too late for stomach removal surgery, an extensive procedure that involves a long recovery, she told USA TODAY.

Doctors are hoping that her body will respond well to chemotherapy but they won’t know for several more weeks.

Her family has started a GoFundMe where people can donate to help her. It had raised just over $5,000 by Wednesday evening.

![]()

Views: 29

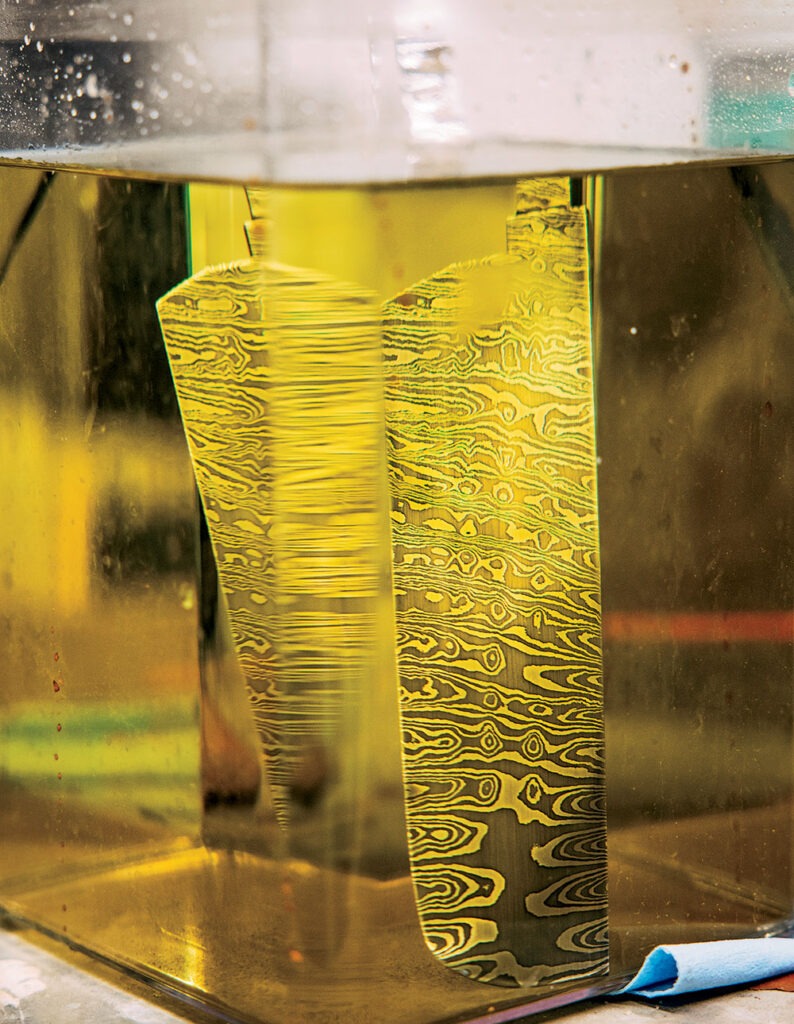

A Knife Forged in Fire.

The author wanted a Japanese-style kitchen blade made for him by hand. What he witnessed was a combination of artistry and atomic magic.

Sam brought out what looked like a deck of tarot cards with nothing on them. No Hermit. No Hanged Man. No Fool. They were gray, thicker than ordinary cards, and clearly heavy in his hands. Inside of them a message waited. He had a long ritual to perform to release it.

As he shuffled the cards, they clattered together, revealing the first hint of their message: They were made of steel. He stacked them and squared up the edges so that all of the cards were nice and straight, nothing sticking out or crooked. Everything neat. The alchemical precision favored by Newton in his dim laboratories.

He clamped them in an industrial vise. Now the cards made a block about the size of a thick paperback book. They would never be individual cards again, these 12 pounds of two different kinds of steel, arranged in alternating layers.

The vise was mounted on a large metal table in the shop that Sam shares with his two brothers, who are fine woodworkers. The shop is in Skokie, which means “marsh” in the Potawatomi language, for these environs were once rich and populous wetlands before they were drained and turned into rows of low industrial buildings like this one and sturdy, modest residential homes. But the brothers have transformed this space into a marvelous cabinet of wonders in which to create whatever they might dream. Much of what is inside could have come from the 19th or early 20th century, great cast-iron machines of fabulous design, embossed with symbols no longer thought necessary to display on slick modern devices. In addition, some of the things in this sprawling realm of clutter might have come from another galaxy, like the ballistic cartridge for the table saw. If you accidentally touch the blade, it senses electrical conductivity and retracts. It’s gone so fast that it can’t cut you. It’s all part of the magic of this place of transformations.

Sam lowered his black face shield and picked up the MIG welder and pulled the trigger. The room lit up to an intensity such that Sam was cast as a silhouetted troupe of antic spiders dancing on the walls and floor and ceiling, sparks flying around him like a cracked nest of hornets and in his hands a burning blue hole at the center of things. All this to the roar of the forge’s fire across the room, heating up toward 2,400 degrees, and the insect chattering of the welder chewing away at liquid metal.

Sam bent over the light, his body curved around it like some sorcerer who’d caught a star and had it pinned there on the bench and was leaning over to examine it and chip away the edges. The bits were falling all around him and bouncing up in little arcs off the diamond floor of heaven. It was positively spooky the way that light stole the glory of the crisp and sunny autumn day outside the open roll-up door.

When he was done and I could look more closely without safety glasses, I saw that he had tacked the cards together with a misshapen bead of melted metal at each end of the stack. As a 12-pound solid oblong block of steel with runes inside, the stack would now be called a billet. To finish it off, he welded a two-foot length of steel rebar to one end to make a handle so that he could hold it.

Sam is afraid of some of his machines in the way that the lion tamer is afraid of his cats. You are confident. You know your skills. You have been doing this a long time. But you know that wild animals are always wild animals, and a false gesture, perhaps an unexpected noise, could set in motion events that could not be stopped. This pact requires utter honesty, complete truth. Sam is harnessing powers that few of us ever encounter in our lives. He’s directing them in order to reach down inside of this deck of tarot cards and transform the very atomic nature of its being. He’s doing what sorcerers do: magic.

John Maynard Keynes, a British economist, owned some of Isaac Newton’s papers. They were about alchemy, which was Newton’s lifelong obsession. Keynes gradually came to the conclusion that Newton “was not the first of the age of reason.” No, Keynes said, “he was the last of the magicians.”

Not the last. We have some right here in Chicago.

Sam Goldbroch is a knife maker. He was getting ready to make me a traditional Japanese-style kitchen knife.

I first met Sam when he was just a kid. I’d see him and his family — his parents, Claire and Bernie; his twin brother, Phil; and their older brother, Simon — at events in the neighborhood near Dewey Elementary School in Evanston where we all lived. My elder daughter, Elena, and Simon began dating in high school and are now married. The boys, as we came to call them, all went into the crafts — Phil and Simon into wood, Sam into food initially. He worked as a chef in various capacities at some of Chicago’s best restaurants, such as Blackbird, Elizabeth, and North Pond. But when he and his wife, Julie Zare, decided to start a family, they realized that a chef’s grueling schedule would not encourage the best home life. So in 2016 Sam began teaching at the Chopping Block, the Lincoln Square school for home cooks. As he taught his students how to use knives in the kitchen, he saw that he really didn’t know anything about them, though he had used them in professional kitchens for 12 years. And with a simple question from one of his students — “What makes a good knife?” — his life was swallowed up into the mysteries of metal and fire and force.

Both the Northeast of the United States and the Northwest have robust communities of knife makers. The American South has even more. Chicago and the surrounding area are just beginning to coalesce into a serious community of bladesmiths. You can see a sample of their wares at Northside Cutlery in North Center, a small and tidy shop of beautiful, handcrafted pieces displayed in a wall-size cabinet Phil Goldbroch made for that purpose. The knives sell for a few hundred to a few thousand dollars each. They are all one of a kind, made by a variety of local bladesmiths.

Sam recently hosted a group of Chicago knife makers for a potluck lunch at the shop. After the meal, Sam cranked up the forge, and one of them, Dylan Ambrosini, crafted a blade while we all watched. Dylan, at 24, is one of the youngest and most talented knife makers in the Midwest. He and Sam collaborated on a nine-inch chef’s knife, which sold for $950 before they could get it on display at Northside Cutlery. Top-end chef’s knives can cost even more. Anthony Bourdain bought one of his favorites for $5,000 from Bob Kramer, a popular bladesmith in Washington State. It brought $231,250 at auction after Bourdain’s death.

In Sam’s kitchen and in the shop, I had seen a kind of knife called a Nakiri. I wanted one. If you’re a knife nut, as I am, that’s all you have to say. Jacques Pépin, the popular French chef, once said that you need only three knives to cook well. “That being said,” he quipped, “I probably have three hundred knives at my house.” People who love cooking can’t always say what makes them fall for a particular style of knife. Most chef’s knives are at least eight inches long, which feels too big for me. Sam had already made me a chopping knife called a tall petty, whose blade was five inches long. “Tall” means that my fingers clear the cutting board, and “petty” means that the blade is short. I use it all the time for chopping, but sometimes it’s too short, as when I have a big onion. I wanted one that was a little longer. The nakiri is ideal for preparing vegetables, which is most of what I do. I have always loved the shape. And I knew that Sam would make his own Damascus steel for this knife. The blade and handle would mate to make a work of art that was an exceptional tool. When I had my first dream about this knife, I woke up and knew that I had to have it.

I decided that I wanted to follow Sam as he made my knife, to understand the process from start to finish. I did not expect that I would stumble upon a mystical and transcendent experience in the making of such a seemingly simple tool.

As my father used to say, there’s a mile of wire in a screen door.

Sam took the billet of steel, holding it by the rebar handle in a heavy blacksmith’s glove, and he carried it to the forge, with its interior of tangerine flame. The forge is a black cylindrical furnace, 16 inches long, as big around as a gallon of paint, and open at both ends. Two propane torch nozzles entered the top to provide the fire. The floor of the forge was populated by glowing white rocks of fractured firebrick. And it roared like a lion. The heat rising from it was so intense that the waves appeared to be dissolving the brick building I could see across the alley through the open roll-up door. I sat at Sam’s workbench. Although I was 20 feet away, the heat on my face was like summer sun.

Sam placed the billet among the white-hot rocks and we waited. He talked of the metal’s need to heat all the way through and “relax.” As we watched, the dull deck of gray cards began to wake up and take on the qualities of a living thing. Among the glowing rocks, it seemed to stir and issued a low, dark color. He had put two kinds of steel in the stack that became the billet, 1095 and 15N20, because he was making Damascus steel, a special kind of steel for swords and knives that combines metals to form beautiful patterns by way of forging and pounding, crushing (called “upsetting”) and twisting. Damascus is not particularly superior to other steels. It’s just prettier. But it has acquired a special mystique because hundreds of years ago, as early as the fourth century B.C., it came into Europe from the East by way of Syria. That steel had a wavy pattern in it. So by analogy, people today call steel that has a wavy pattern “Damascus.” The Crusaders were armed with Damascus blades. It was said that theirs were quenched in the blood of dragons. And it was also said that those blades could do battle with the Saracens and afterward still sever a feather floating in midair.

If you want to know what rock is like deep in the earth, you can see it here in the shapeshifting of the metal. These are the energies that we are not used to in the quiet simmer of our daily lives.

I watched the forge. It took a long time, but it had our attention the way a green shoot would where only some damp sand had been seen before. Something was changing. Transformations were coming. If you want to know what rock is like deep in the earth, you can see it here in the shape-shifting of the metal. These are the energies that we are not used to in the quiet simmer of our daily lives. The energies of the deep earth and the high sun, the two sources that power our planet.

Half an hour passed, and now the billet was no longer gray. It had taken on the look of a bright confection of orange marzipan. Sam put on his blacksmith’s gloves. The billet was so hot that he wore glasses tinted against infrared radiation. He lifted the billet out of the forge for the first time to check the color of the metal. The rebar sagged like a fishing rod with a swordfish on the line. He wasn’t pleased with that, but he liked what he saw on the billet, and so he swung it over to the 12-ton hydraulic press just a few feet away. The billet landed on the compression platform. Holding the rebar in his left hand, he brought down the handle on the press with his right, moving the square metal die down to gently tap the mushy billet with a few tons of pressure so that he could see if it had been heated through and through. He had to make sure that his welds were holding the cards together. The smith calls this process of initial compression “forge welding,” because if everything is right with the stack, the cards will meld into one solid piece.

As the cards of metal were deformed and compressed, the surface of the billet rippled and changed color as if in emotional response to the extremes of heat and force, turning gray and deeper orange and shedding dark flakes of oxidized metal. Sam tapped the handle and added more pressure. Waves of dull gray cascaded across the surfaces and calved off and fell to the floor. But the billet held together. First success. It had cooled enough now that Sam had to return it to the forge to reheat it to a working temperature of about 2,300 degrees.

While it was heating, Sam unbolted the flat dies from the press using a socket wrench. Dies are the parts of the press that actually make contact with the hot metal. He exchanged the flat ones for more rounded ones that are called drawing dies. They would draw the billet into an elongated shape and help start to flatten it.

When the billet was hot enough once more, Sam began compressing it more aggressively to transform it into what he called a bar. In the middle of this, the rebar handle melted, menacingly clattering to the floor, ringing and dancing, and Sam stepped gingerly back to let it settle, then continued his work by lifting the billet with heavy tongs. There was no stopping now. He would succeed or fail by the skill of his hands and his knowledge as a bladesmith.

A natural, lifelong student of anything interesting, Sam got his start by trying to answer that question of what makes a good knife. He began to buy knives of good quality, but old and beat up, to restore them. He talked to knife makers and chefs who knew about knives. He took blacksmithing classes in which he began to acquire a feel for metal, not as the solid that most of us are used to but as a substance every bit as malleable as potter’s clay. He began to get a feel for taming the fire.

Heating and crushing now with more and more force, Sam gradually transformed the billet into a crude bar of steel so long, about a foot and a half, that it hung out either end of the forge. He then took the bar back to the metal table and clamped it into the vise. He put on his ear protection and picked up an angle grinder. At 1,000 degrees, the steel had gone dark.

Sam turned his grinder to cut from the other side, and an orange volcano shot up to the ceiling. He explained that you can tell the kind and quality of steel you’re working with by the color and shape of the sparks.

To make my little six-and-a-half-inch nakiri knife, Sam didn’t need all 12 pounds of steel that he’d started with. But the process of forging Damascus steel is so difficult and time consuming that he wanted to make as much as possible in a single batch. As he began cutting the bar in half, orange sparks cascaded down, elves of fire skipping across the concrete and dancing away into the sunlight in the alley. He turned his grinder to cut from the other side, and an orange volcano shot up to the ceiling. He explained that you can tell the kind and quality of steel you’re working with by the color and shape of the sparks.

Cutting through the bar took the better part of an hour, as he heated it to soften it and attacked it again and again with different tools. After destroying several angle grinder blades, he brought out a chisel he’d forged in a blacksmithing class and began hammering it into the cut he’d made in the bar. The making of Damascus steel takes a heavy dose of artistry and craftsmanship, and if one approach doesn’t work, you try another and another until the thing in your head becomes a thing in the world. At last he had the metal bar hot and nearly severed and clamped in the vise, and with his blacksmith’s hammer, he swung for the fences and knocked half the billet across the room. Fortunately, no one was in the path of the projectile, which landed, smoking, on the floor by the forge.

When the two black hunks of metal had cooled to a few hundred degrees, they took on an almost melancholy gloom of blue-gray, dashed with a distemper of rust, and their random-seeming warts and scars gave them the aspect of objects that had made a long and lonely journey through space, ending with a fiery entry into our world. Only the squared-off shape of these meteorites betrayed the hand of man.

Sam picked up one of the chunks with his tongs, saying, as unlikely as it seemed at that moment, “There’s a knife in there. That’s all that matters.” He also mentioned that the worst accidental burns in a forging shop occur when the metal has cooled off to black and is still at several hundred degrees. The visitor learns to touch nothing.

Now that he was working with a billet that weighed six pounds instead of 12, he could proceed much faster. Moving from forge to hydraulic press, heating and upsetting and turning, occasionally changing dies to different shapes, Sam gradually formed the bar into a piece about 16 inches long and an inch and a quarter square. Some time before, Sam had acquired a rusty old-fashioned monkey wrench. He had welded a piece of steel round bar to the head to make a long and heavy wrench for one specific purpose: twisting a bar of hot Damascus steel. Now he heated the bar and clamped it with the hydraulic press just enough to immobilize it, not enough to deform it. Then he fitted the adjustable wrench to it. Because the bar was now square in cross section, he could maintain a grip on it, as with a wrench on a nut. But when he went to twist it, he managed to turn it only halfway around. It wasn’t hot enough.

He put it back in the forge and this time heated it until it was in a yellow rage of photons. Again, he fitted the wrench to the glowing end. And then, using his entire body and the leverage of the long-handled wrench, he began twisting and twisting. The metal shed great gray flakes, and the yellow bar gradually turned orange, looking like a twist of taffy as Sam put all of his effort into the now-helical bar until it would turn no more. It was as if he were doing battle not so much with steel but with fire itself, placing the bright yellow bar in the press and then wringing the light right out of it, for that’s what it was, a blade of bright light that he strangled until it went black.

Then he put the bar back in the forge and did it all again. He repeated the process five times, and as the twists grew into a tighter and tighter pattern, the steel began to bend upon itself and undulate like an incandescent banded snake.

When Sam thought that the metals had thoroughly mixed, he placed the bar in the vise and picked up the angle grinder.

“I’m going to give you a nice center cut,” he said, meaning the place in the bar where he’d find the best pattern of steel.

He took a wooden nakiri template from a board on the wall where he kept the blanks of all the knives he made. He placed it on his anvil and traced its shape with chalk on the bar to get the length right for blade and tang. The tang is the slim projection from the blade that he’d fit into the handle. Using the heat, the press, and a hammer on the anvil, he flattened the metal into a vague, cartoonish semblance of a rude asteroid-black knife that my four-year-old granddaughter, Annelise, might have drawn in charcoal. He clamped it in the vise to let it cool. He occasionally pointed an infrared meter at it to check the temperature. When it was cool enough to handle, he took it to the bench and again traced the nakiri shape onto the rough alligator surface. Then he went to the band saw and cut away as much metal as he could around the silhouette. Even though I had earplugs, the noise drove me out to the alley.

Sam was doing all this after taking a weekend forging class outside of Philadelphia. He’d driven 12 hours home, getting only five hours of sleep. Then he wrestled this demon all day, almost eight hours of back-wrenching work, until he got what he had envisioned in his head. It was roughly the right shape. But it was still scabbed black and ugly. Day one was done.

As if in rebellion against the taming of the fire, all night long the lightning lit up the low gray udders of the clouds, the wind milking them here and there for their pitiful rain. What epic history lay beyond the thunder’s crack and groan?

On the second day, Sam retired to the grinding booth, an enclosure he had built for his power sanding. The belt grinder is a machine of admirable complexity that can turn every which way while keeping a six-foot loop of sandpaper revolving on drums, allowing Sam to make shapes such as Western knife handles. He has to wear a respirator, a heavy apron riveted in brass, gloves, and noise-canceling headphones.

I saw Sam at his best in there. He stood in his armor, confronting a clearly dangerous and indifferent machine of stupendous mechanical capacities for removing any material that came near it, including human flesh in large bloody quantities if he slipped up. It’s a bit like a whirling wall of razor blades. Sam put both hands into this, holding something fairly small — it might have been a knife or a handle.

He is a big man, solid and steady on his feet, with wide shoulders and strong arms. He is soft-spoken, modest, and understated, a kind of gentle giant. I’d see him Saturdays at the summer farmers’ market with one or the other of his two children on his shoulder. If you met Sam, your first impression might be of calm and strength, control and competence. He’d happily show you what he can do with hammer and tongs, and you’d understand the deep dichotomy and even mystery that powers his mastery of energy and matter. What he does is simply so self-evident in the end that it cannot be questioned. When he’s done, what he puts in your hand is self-explanatory. He does not apologize. He does not explain or boast. He does not have to. It’s in your hand. And if you met him, you’d wonder: What gives him such a solid platform?

I think Sam’s mastery grew out of a catastrophic incident in his childhood. He had struggled with fire when he was young, and not in any artistic way.

I think Sam’s mastery grew out of a catastrophic incident in his childhood. He had struggled with fire when he was young, and not in any artistic way. The story of that struggle belongs to him and Simon and Phil, who went through it together, so it is not mine to tell. But I can say this much: They were trapped in an out-of-control fire when they were kids. They survived. Their parents did not.

When he came out of the grinding booth, Sam had the metal in the right shape and even close to the right size. This was called the rough grinding of the knife. Now he had to set the bevel, the angled portion of the blade that would terminate in the cutting edge. He did this with hammer and anvil, man against steel, as in images of 19th-century industrial infernos. The hammer rose toward the ceiling and then Sam put his whole back into it as it came ringing down on the steel. When he first brought the blade out of the forge, it was a tiger burning bright, and when he straightened up with the shape he was after, the black stubbly silhouette looked as if all it needed was a little stamp on the edge that said “Made in Hell.”

All morning long, a small heat-treating oven, actually a kiln that could have been used for ceramics, had been warming up. Now it had reached 1,650 degrees, the temperature at which to begin the process called “normalizing.” All of the forging and pressing and hammering and twisting of the metal had confused the internal crystal structure of the steel and introduced weird stresses among the grains.

But since the knife now had the exact shape that Sam wanted, he wouldn’t need to do anything violent to the blade again, except one final explosive act. To prepare for that, he first had to heat it back up to the point that the steel could, as he explained, relax again and release the tensions within, so that rather than being, at a microscopic level, like broken and jagged sea ice, the metal would be like a quiet millpond.

He placed the blade in the oven and closed the door. He set the timer for 10 minutes and went back to his bench to begin work on the handle. The artistry of this knife was all Sam’s doing. I had given him absolute control. But I’d spied a particular piece of wood among the materials he keeps for making handles. It was a rare Australian eucalyptus called vasticola burl, and when I’d first pointed to it, Sam smiled and said, “Oh, I love that wood.” He picked it up. It was just a block, perhaps six inches long and two inches square. He wiped some oil on it with a paper towel, and it seemed to glow.

“It looks like fire,” he said.

The fire again. He’d had his taste of fire when he was a child. And now it was in his blood.

The block was too wide for the Japanese wa handle that he was going to make, so we went into a giant room with an array of limb-snatching machines, and he cut it to size on a 1912 band saw that was taller than we were. Back at his bench, he searched in the drawers full of materials for handles and came up with a nicely patterned piece of buffalo horn for the ferrule, the protective ring between handle and blade.

“This is good,” Sam said. “It’s usually just black.”

The timer went off, and he took the blade out and put it in a rack to cool. He turned the heat down to 1,550 degrees, and when the blade had cooled, he returned it to the oven. After another 10 minutes, he put the blade aside again to cool and turned the oven down to 1,450. He repeated the 10-minute heat treating and set the blade aside once again.

“It’s still not a knife,” Sam insisted.

It was not yet good steel. It couldn’t be sharpened to take a cutting edge, and whatever edge you might put on it wouldn’t hold. It was useless for the kitchen, which was where I wanted to take it. To eat, let’s not forget. For what is a human but a transport channel for energy? And our energy comes from food. Lovely, gourmet food prepared with a fine knife. The qualities we need in a knife to create that food come from the atomic structure of the steel. But for the moment, what we had here was like a pig wallowing in mud and claiming to be cassoulet.

Sam stepped up to the oven, beside which the blade had been cooling. The oven had reached 1,475. He put the blade in and closed the door.

A slender, rectangular metal vessel sat upright on the floor by the oven. It looked somehow military, as if meant to shoot a rocket. It was filled with Parks 50, what’s known as a high-speed oil and designed for this purpose. After 10 minutes of heating to 1,475, Sam took the blade from the oven with heavy tongs and gloves and plunged it into the oil. A cloud of smoke rose to the ceiling, and a searing sound filled the room like a basket of snakes.

“This is the moment of truth,” Sam said, holding the tongs and looking away from the smoke. “This is when it becomes a knife.”

“This is the moment of truth,” Sam said, holding the tongs and looking away from the smoke. “This is when it becomes a knife.”

The quenching is a pressurized moment on which everything else turns. He cannot flinch. He cannot fake it. Like the free solo climber, he cannot make mistakes. The mere hint of a ping with the knife in the oil, and he’d have to go back to the other half of the blackened billet and start over. Because the knife would have fractured. Hard to believe, but at this point, if Sam dropped the knife, it could shatter. Some American knife makers have even taken to having a quenching ceremony to mark the birth of a knife. Some of them also think that you can quench properly only while facing north. Sam doesn’t hold to those ideas. You do your best and try to have more skill than luck.

The small heat-treating oven sat atop another oven that looked as if it wouldn’t be out of place in a 1960s kitchen. It was a tempering oven. Sam had set it to 400 degrees, and now he put the knife inside for many hours of tempering, which would finish settling the structure of the metal and would reduce its hardness to the sweet spot where it could be easily sharpened and would also hold an edge. Sam could do nothing more with this blade until the tempering was finished. So he would turn to other projects.

Before I went home that second day, Sam said, “I’ll finish the belt sanding tonight and leave about 10 percent of the hand sanding for the morning so you can watch. Assuming you like to sit there and watch people sand stuff.”

Steel is not steel. It is a chameleon, completely dependent on its environment. At temperatures such as Sam was using, it is a glowing portal to the world of the atom. Steel is iron mixed with carbon and some other elements, depending on what kind of steel you want. I had asked Sam to make me a high-carbon knife, which means that, by technical definition, at least 0.6 percent of its atoms are carbon. In practical terms, it means that it’s not stainless steel and will rust if you don’t take care of it. Sam and I like to take care of our knives the way some people like to take care of their motorcycles.

Taking care of a knife is pretty simple. You strop it before each use. You don’t throw it in the sink. You wipe it off and put it in a safe place when you’re done — a knife block, for example. And we would chop down telephone poles with it before we’d put it in a dishwasher. Then again, to qualify as a master bladesmith with the American Bladesmith Society, you have to chop a wooden two-by-four in half two times with a knife you made and then still be able to shave with it. The rules for that qualification test clearly state: “The test knife will ultimately be destroyed during the testing process.”

The knives that Sam and his fellow Midwestern smiths make, passed from hand to hand with care, from mother to son to uncle to granddaughter, could last a thousand years, by which time every speck of high technology we know today will be dust. But the reality is that if a knife maker has become too famous, you simply can’t get his or her knives any longer.

Iron atoms form crystals of various kinds, atoms connected electrically to one another. Iron atoms are like little magnets, having a north and south (positive and negative) end. So they can arrange themselves like those toys for children, magnetic shapes to create pleasing patterns.

When carbon mixes with iron, the smaller carbon atoms occupy the spaces between iron atoms. The crystal arrangement of the iron atoms changes to accommodate the carbon. Different crystal arrangements give the metal different properties. Think of it as bread. It’s like deciding what kind of bread to make. White bread. Sourdough. Hard Lithuanian black bread. Fluffy Mexican bolillos. So goes the saga of steel. The tarot cards Sam dealt at the start of this process were 1095 steel, which is iron with between 0.95 percent and 1.05 percent carbon, and 15N20, which is iron with nickel. Mixing the two is popular for making Damascus and produces an attractive pattern and a very nice edge.

As a lover of good food and good kitchen tools, I don’t need to know much about metallurgy. A bladesmith like Sam can take care of that. But I find this stuff fascinating, these amazing transformations. I like to know what’s going down in the atomic world that will blossom into these beautiful patterns of his blade.

As I watched Sam work, I kept having the impression that he was trying hard to erase something — the traces of the fire, the encroaching flames, the blackened body of the meteorite after its travels. But the erasing was also an act of creating. Michelangelo said that the block of marble contains a man, and all you have to do is remove the rock that isn’t part of the man, and then you will have your sculpture. So Sam said, “There’s a knife in there. …” And in this attitude of seeking, there is a humility that does away with the myth of the conquering hero or the towering artistic genius.

Sam does not see himself as the creator of the knife. He sees himself as having found it inside of this other, most unlikely object.

Sam does not see himself as the creator of the knife. He sees himself as having found it inside of this other, most unlikely object. As he worked, he let the steel tell him things. He followed what the material suggested rather than sticking to a predetermined plan. He was facilitating the process. He was the sorcerer. He did not invent magic, did not really make magic, but he employed magic. And with the rackety dance of hammer and tong, he was urging the knife into stelliferous being. In the process, he was also taming the fire.

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, an ape not all that different from us created an edge by fracturing one rock with a blow from another. Make no mistake. Such a knife is sharp enough to shave with. And at a stroke, the woolly mammoth could fall apart into bite-size pieces. It didn’t change everything, but it laid a dense, high-calorie, protein-packed feast on our table that allowed the relatively small inner workings of our gut to extract the tremendous amount of energy needed to grow these giant billowing brains we have. In a sense, the knife marked the birth of civilization.

When I came in the next morning, while I did not feel that I had missed anything crucial (Sam sitting and sanding), the knife was now a revelation. It was the right size and shape, and it was all silver. It looked like a real knife awaiting a handle.

“Wow,” I said.

Sam smiled. Then, with a sly look: “Let me show you something.”

He carried the blade to the room of giant machines. Against one wall a sink was set up with gallon-size square beakers of colored liquid, one black or dark blue, one gold. “We’ll do a two-stage etch and see what we’ve got.” He washed the blade and cleaned it with Windex. He then put the blade into the dark solution. He set the timer on his watch, and when two minutes were up, he again cleaned and rinsed the blade and put it in the golden liquid. I knew that the dark fluid was ferric chloride. I asked what the golden liquid was. Sam reached to a shelf behind the sink and brought down a half-gallon bottle. It featured a cartoon alligator and was labeled “Gator Piss.”

“What’s in it?” I asked.

Sam shrugged. “Proprietary, I guess.” He left the blade to etch and went back to his bench to tidy up. “But it works,” he said.

The trade name might seem odd to those who don’t know the history of Damascus steel. Ancient Afghan makers, for example, quenched their blades in donkey urine. Some makers during medieval times believed that only the urine of redheaded boys should be used. Other Asian smiths prescribed heating the blade until it looked “like the sun rising in the desert” and then shoving it “into the body of a muscular slave.” About quenching by murder, Sam said simply, “I don’t make weapons.”

Half an hour later, he took the blade out of the Gator Piss and washed it. He held it under the lamp. We could clearly see the Damascus pattern, with its contour map of dark hills and bright craters, its sinewy valleys and far landscapes. And we could spot his signature, or maker’s mark, which he’d electrically etched on the blade. And as with looking through a microscope, the longer you looked, the more you saw.

Sam took the blade back to the bench for finer and finer sanding. “You don’t want to make it too fine,” he said. “Or the pores will close up and you’ll start to lose the sharpness of your pattern.” He would take this Damascus to 800 grit.

He had more polishing to do, more etching. The handle was a simple shape and Sam knew it well. He’d sand and polish it, and then the eucalyptus would really look like fire. He’d glue the tang into the handle. And of course, he would sharpen the knife and shave the hair on his arm to test its razor edge.

Outside the open door, I could see that the day was high and clear with light-year blue and upward-tumbling cumulus clouds that mirrored the Damascus pattern churning in the blade.

The quenching of anxiety and stress through ordered, repetitive, directed, and meaningful physical motions is an effect well known among neuroscientists and others who work with human brains and nervous systems. The rhythmic movement is soothing. Sam had tamed the fire inside and coaxed it outside to create a work both useful and beautiful. A palliative process that would give rise to a tool that would feed us and satisfy our sensibilities with its physical beauty while doing so. All of human history would thereby be embodied in a single work of art.

On the third day, when Sam presented me with the finished knife, it was so beautiful that it took my breath away. I brought it home and cut some onion for my wife, who was making dinner. The knife slid through the flesh with no resistance. It felt like cutting air. I rinsed it and wiped it dry and during dinner we propped it up in its black velvet case and we stared at it like early humans in a cave somewhere, watching fire.

![]()

Views: 24

Breakfast of Champions. I went hog wild during the month of December. Gained almost 10 lbs. So, I went on the South Beach Diet. I’ve lost 8 of those pounds so far.

My Breakfast consists of five pieces of celery, I mix a pure natural peanut butter with a protein nut mixture of seven different nuts.

Lunch usually consists of a wrap of Low sodium Turkey, Ham, and a slice of Pepper Jack Cheese. Dinner can be chicken Mexican Soup, Chili, or fish.

![]()

Views: 67

MC’S Family Christmas Decorations 2023. Part 2. Living Room. It took a few days but here’s our Living Room. Our Living room does feature the fine furniture we have bought over the years.

But the way my wife did the decorating is something else. The first picture you see is what she did with our bookcase.

Next three is the start to finish of decorating our tree

Of course the fireplace.

The entrance way below contains a reproduction piece that was made by a famous maker of reproduction furniture. It took a years wait before he was finished.

Front Porch.

More photos in the comment section.

![]()

Views: 43

Looking for folks to write some good articles on Food, Music, and Feel Good stories. We here at Koda invite folks to add articles to our website. These are non political articles.

We feature Music, Food, and feel good articles. If you would like to try, contact me at

ledbed12345@gmail.com

We use wordpress here, if not familiar we will teach you.

![]()

Views: 34

Fall fest and Thanksgiving. Well we jumped from AppleWorks to Fall Fest and Thanksgiving. Enjoy our decorations.

![]()

Views: 53

We love our black accent pieces. We tend to use black chairs and tables in our decorations. Some of the pieces are seasonal and some are year round. I can’t take credit. My wife usually picks out the items and we will then either restore them or change them all together.

Some of the pieces are Antiques, some Vintage, and some are just cheap pieces of furniture that add that special touch.

The ugliest piece we ever bought. Paid $3.00. I couldn’t do anything with it.

![]()

Views: 32

‘All the neighbors know who she is’: How one woman built a flower farm across eight yards.

Rachel Nafis, waist-deep in corncockles, cut the blush-colored flowers growing in her neighbor’s yard as her eyes wandered to the front door.

“I hope Tom comes outside to say hello,” she said as she placed the cut stems in a bucket of water.

Soon, a smile crept across her face as Tom Weaver opened the door and wheeled himself onto the porch.

“It’s so wonderful to see flowers growing outside my window,” he said from his wheelchair. “I love seeing them. They smell so good.”

For three years, Nafis, a one-woman florist, has grown sunflowers, dahlias and corncockles outside Weaver’s home, one of eight neighbors who have donated their yards to Psalter Farm Flowers, a loose collective of cutting gardens that is a draw with San Diego flower shops, event florists and bouquet lovers.

Not surprisingly, the flowers burst out of yards in various states of bloom due to the seasons. Around the corner from her home base, across the street from Webster Elementary School in City Heights, yellow and pink strawflowers and delicate blue scabiosa pincushions grow tall in raised beds.

A quarter mile in the other direction, pink bellflowers and the conclusion of fragrant sweet peas grow in neat rows behind the rental home of Sophie Thompson.

“All of my gardens are in places where people cannot care for their yards the way they would like,” said Nafis, 36. She also cultivated the alley behind her 800-square-foot home. “I feel I’m adding value to their homes and our neighborhood.”

Thompson agreed. “I don’t know much about farming itself, but I’m impressed how Rachel has increased the biodiversity,” she said of the neighborhood, which is among San Diego County’s poorest. “There is less infrastructure and greenery, fewer markets and more liquor stores here. But she’s taught us that all neighborhoods can be beautiful.”

Mindful of trends but not beholden to them, Nafis prefers growing seasonal flowers that speak to her. “I like fragrant flowers like roses, sweet peas and scented geraniums,” she said of the flowers blooming in her front yard and backyard. Right now, the cool season flowers — snapdragons, strawflowers, sweet peas and poppies — are transitioning to ranunculus and anemones and summer annuals like dahlias, zinnias and cosmos. “I try to grow things that don’t ship well,” she said. “Most florists are getting things imported from out of the country. I like to grow things that would get damaged in shipping or not last that long and florists would like to source locally.”

To passersby, the colorful cutting gardens stand out against the lawns, many of which have turned brown after California was asked to cut back on water during the drought.

Conserving water is important to Nafis, who subsidizes many of her neighbors’ water bills. “We have everything on a drip system and timers,” she said. “I also use a lot of mulch, which helps to retain water and take care of my soil.”

Although she likes working alone, Nafis’ quiet presence resonates throughout the neighborhood. Shortly before Weaver’s brother, Don, died in 2021, the family moved his hospital bed next to the window so that he could watch Nafis working in the garden.

“It’s extraordinary to be present and so deeply a part of the neighborhood,” she said of the neighbors, dog walkers and parents who greet her as she walks from house to house with her flower buckets and shears.

“These have been meaningful life relationships. We’ve had two people pass away since I started this,” she said, her voice breaking. “When you open yourself up to relationships, it can be messy, but I think you can also be amazed by the good things that can happen. My business model is very fragile but not as fragile as you might think. I’m not leasing land with a farm with a five-year commitment. I think that would be ideal, but that’s not a possibility. We couldn’t afford it, but we are grateful to own our house and be able to make a living through this creative shared-land model.”

“All the neighbors know who she is,” said Kristen Kellogg, a nurse practitioner who donated her yard. “We have five sisters in the neighborhood who live in three houses, and when their mother passed away, Rachel was able to make arrangements for them. They knew the flowers were from Rachel, which meant a lot to them.”

At a time when many people feel isolated and alone, Nafis dropped a written request in Thompson’s mailbox, asking if she could use her yard. “She has become a good friend,” Thompson said. “I have been in and out of some hard transitions, and I have texted her late at night and even asked her if she could come over and help me move a king-sized mattress.”

Nafis, a mother of three young boys, grew up in western Michigan and worked as an ER nurse for 13 years before leaving the profession during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It was tough,” she said of working as an emergency room charge nurse during the pandemic. “My kids were all home and my husband’s workload increased. The hospital was asking me for more hours. I was burned out. We both worked multiple jobs for many years and decided we couldn’t do it anymore. Changing careers was challenging and such an identity shift from nursing to farming. It was like low-wage manual labor at times. But I couldn’t have imagined doing anything else when we were at a breaking point. I enjoy what I’m doing now.”

Given her small-business success — she’s doubled the farm’s annual revenue every year since its inception in 2019 — Nafis notes that she and her husband, Chris, a pastor, failed miserably in their previous attempts at farming a small community-supported agriculture farm on a vacant lot in Lemon Grove in 2012 and a 45-acre ranch in Jamul in 2013.

“Everything was eaten by rodents in Jamul,” she said. “We lived in a trailer and were both working our day jobs. Anything that was a success was eaten. Even though it was difficult, I think it has been a part of my success.”

In 2014, the couple purchased their home in City Heights and, when not working, tended to a vegetable garden and chickens (that were leftovers from the Jamul ranch). When she planted a row of dahlia tubers in her vegetable garden, she fell in love with the gorgeous ball-shaped blooms, which when cut, would last a week in water. Soon, she decided to experiment with traditional farming, turn her backyard into a cutting garden, and use her neighbors’ yards as satellite farms.

“The model I have created is very relational-based,” she said. “Every house is different based on my relationships with my neighbors.”

Walking through the neighborhood, the flowers are a touchstone that connects her to neighbors and elevates her mood. “I often experience euphoria working with beautiful flowers all day,” Nafis said. “I also appreciate that flowers are appropriate to mark every occasion, from grief and loss to heart-bursting celebration, to long difficult days that drag on forever.”

Nafis thinks her business model resonates with her clients because they care about the environment. “I don’t use any chemicals,” she said. She also utilizes a no-till method that conserves water, feeds the soil and creates a natural habitat for birds and beneficial insects. “Sustainability matters to people,” she added.

The other allure of buying locally grown flowers is the exceptional quality of freshly picked flowers. “There is a real vibrancy when flowers are picked 12 to 24 hours before purchase,” Nafis said. To illustrate this, she collected a chocolate-scented geranium and invited a sniff. “That’s what flowers lose in shipping,” she said.

Nafis also can grow flowers her clients can’t easily find anywhere else. “You can only get corncockle at a local farm,” she said. Other rarities include Iceland poppies, garden roses, foxgloves and lisianthus.

In September when the summer season ends, Nafis will take a break and tend to the soil.

“It’s hard for me to manage, even though I get better every year,” she said. “Plants are living things, and so many different variables are involved: losses to insects and rodents, succession planting. The cutting of flowers is labor-intensive because they need to be cut twice a week, and that never ends. Even when I’m not selling, I need to deadhead the flowers so they don’t go to seed.”

The hard work has taught her to create boundaries for herself such as inviting her subscription clients to pick up their bouquets on her front porch instead of driving all over San Diego to deliver them herself. But for her neighbors, the close bonds remain.

“She has made such an impact on the neighborhood,” Kellogg said. Flowers may be transient, but friendships can last a lifetime.

“Yes, she’s a florist,” she said. “But it’s about a lot more than just flowers.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

![]()

Views: 38

Best road trips in all 50 states.

A great road trip is hard to beat. Exploring by car allows you to immerse yourself in the journey rather than hurrying to get to a specific destination. Road trips in the United States are so popular that an estimated 50 million Americans embarked on one in 2019, according to a AAA Travel survey. From cityscapes to untouched wilderness, you can see it all in the country with boundless diverse landscapes. Take a look at the best road trip in each state for some extra travel inspiration.

Take in Alabama’s beautiful white sand beaches on a road trip along the Gulf Coast. Cruise along Alabama State Routes 180 and 182 — which link the state’s borders with Mississippi and Florida. If you need a place to stop and dip your toes in the water, both Gulf Shores and Orange Beach are home to plenty of hotels and restaurants, not to mention sandy spots to lay a towel. Make sure you grab lunch at The Hangout, a beachfront seafood restaurant with live music and epic views. Extend your trip by heading north through Mobile, Alabama’s port city, to Montgomery, the state capital.

Road Trip Highlights: Although the entire drive is scenic, stop at Gulf State Park for biking, paddle boarding, and kayaking. Here you’ll find the Gulf State Fishing and Education Pier, the largest on the Gulf of Mexico.

If you’re looking for a road trip with breathtaking views around every curve, you’ve found it. The stunning Seward Highway starts in Anchorage, which lies just south of the coastal town of Seward, and is an adventurous journey you can’t miss. Pass the dramatic shores of Turnagain Arm, a waterway in the northwestern Gulf of Alaska, before reaching the dramatic Chugach Mountains. Once in Seward, you’ll have the chance to admire Resurrection Bay, a favorite among photographers, and the Kenai Mountains.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop at the Kenai Peninsula, home to Kenai Fjords National Park. The Exit Glacier in Kenai can be reached by road and offers hiking trails with gorgeous overlooks.

No trip to Arizona is complete without witnessing the iconic red rock formations of the American West. Monument Valley Scenic Road is the nickname for Highway 163 that runs for 27.7 miles through the tall, staggering sandstone structures of northern Arizona. The alien terrain is eerily empty, and this scenic drive is sure to take you on a journey unlike any other.

Road Trip Highlights: Add an additional 17 miles to your trip when you stop at Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park to learn about the Navajo people and discover famous red clay buttes. The loop drive features two hiking trails and 11 lookout points. Also be sure to visit Alhambra, a volcanic core on the side of the road and the village of Mexican Hat to see the sombrero-shaped rock formation. Both make for perfect photos.

Start your road trip in the Ouachita Mountains in Hot Springs. Stroll around the historic downtown area and wander through Hot Springs National Park. When you’re done soaking in the natural springs, dry off and hop back in the car to head northwest. There are two different routes you can take. Outdoor enthusiasts should head towards the mountains of Ouachita National Forest to take a hike or even camp for the night. City lovers, on the other hand, should take the route through Little Rock, the state capital that sits on the Arkansas River. Continue north before ending your trip in the Ozark National Forest — an area that spans 1.2 million acres.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop at Mount Magazine to see the best of natural Arkansas. Take the scenic drive to the peak, where a charming stone overlook will greet you.

Take the ultimate California road trip and travel the entirety of State Highway 1 — more famously known as the Pacific Coast Highway. Start at the northern border of California near Oregon in Crescent City. Travel south until you reach Redwood National Park where you should stop to take in the unique scenery. Multiple beach towns and both national and state parks litter this route, and you could spend weeks or months exploring every coastal corner. Keep going and you’ll pass through such cities as Santa Cruz, Monterey, Santa Barbara, Malibu, Los Angeles, and San Diego just to name a few.

Road Trip Highlights: While there are many iconic stops along this route, be sure to stop in Monterey, a quintessential Californian beach community located about 100 miles south of San Fransisco. Here you’ll find attractions like Cyprus Point Lookout, Pebble Beach, and the charming town of Carmel-by-the-Sea.

Winding through the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, the Million Dollar Highway is a journey through time and nature. Drive through mountain passes and old mining towns as you journey from Ouray to Silverton. The terrain is challenging, but the views are worth a million bucks — hence the road’s name. Many people drive the Million Dollar Highway to earn bragging rights, but exploring the mountain towns of Ouray and Silverton are worth the trip alone too. Located in a box canyon, Ouray is a charming town with a historic street and nearby ice-climbing park. Meanwhile, Silverton is a little sleepier with charming restaurants and antique shops.

Road Trip Highlights: Rest your weary body in geothermal heated mineral pools at Ouray Hot Springs outside of Ouray.

First established in the 1630s by the Dutch, this coastal region of Connecticut features plenty of unique historic sites for travelers. Take U.S. Route 1 starting in Greenwich, a classic New England town by the sea. Pass sailboats bobbing in the ocean and lighthouses dotting the coast, until you reach New Haven. There, tour the historic grounds of Yale University, visit a museum, or picnic in one of the many expansive parks. Head up the coast until you reach the Rhode Island border, stopping at the small coastal communities along the way.

Road Trip Highlights: Don’t miss your chance to tour the hallowed grounds of Yale, the third-oldest college in the country and one of only nine colonial colleges that were chartered before the American Revolution.

Discover the charming countryside of the Brandywine Valley in northern Delaware on the border of southeastern Pennsylvania. Boasting sprawling estates and beautiful gardens, this area was once home to some of the wealthiest families in America and earned the nickname “Chateau Country” due to heavy European architectural influences. The easiest way to explore Brandywine is by taking Routes 100 and 52, which loop through the quiet countryside. Enjoy a slice of American history as you pass through the wildflower-lined roads and proud estates.

Road Trip Highlights: Visit Nemours Mansion and Gardens, a 300-acre classical French estate that will transport you to Europe in an instant.

Although Florida has seemingly unlimited road trip opportunities, get off the beaten path and head to the panhandle of the Gulf Coast for a relaxing tour of the Emerald Coast. Named for its shimmering turquoise waters, this coastal region is dotted with small beach towns that will tempt you to pull over mile after mile. Start at Fort Walton Beach and drive across Okaloosa Island on State Road 30A. Observe parasailers, kayakers, and boaters enjoying the sun as you drive over this narrow strip of sand — or maybe park the car and join them on a watery adventure.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop at Alys Beach and Rosemary Beach — exclusive resort towns with delicious restaurants and beautiful homes. Once there, leave the car parked and rent a bike to explore instead.

If Georgia is on your mind, head down this rural road trip through the mountains to explore the state’s completely underrated interior landscape. Start in Atlanta and head northeast up I-85 towards the small town of Helen. Along the way, pull over at Lake Lanier, one of the best-kept secrets in northern Georgia which features resorts, live music, bars, and boating. Continue north through the mountains and visit quaint mountain towns before stopping to rent a cabin for the night. Enjoy your morning coffee with views of fog rolling over the rugged landscape as you consider moving here permanently.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop in Helen for a night or two. Known for its Bavarian-style buildings, river tubing, and epic hiking trails through the Chattahoochee National Forest, this town has something for everyone.

If you’re looking for adventure in Hawaii then take a drive on the famous Hana Highway around the island of Maui. Start in the town of Kahului and continue east through Pā’ia, stopping at Ho’okipa Beach to catch a glimpse of native sea turtles. Carefully continue along winding roads that hug cliffs and dangle over the sea. This trip isn’t for the faint of heart due to sharp turns and one-way bridges, so make sure you stay alert. Protected forests and state parks will greet you towards the end of your drive. Wai’ānapanapa State Park is a great place to wrap up your trip. With black lava sand and tidal caves to explore, this quintessential Hawaiian beach doesn’t disappoint.

Road Trip Highlights: Make roadside stops for waterfalls like Twin Falls, an easily accessible, secluded area about 20 minutes from Pā’ia.

See the diverse landscape of Idaho with this road trip through the southern end of the state. Start in the capital, Boise, continuing east on I-84. Leave the jagged mountains and downtown skyline behind you as you head towards the famous Shoshone Falls Park near Twin Falls. Known as the “Niagara of the West,” these falls are breathtaking and measure 45 feet higher than Niagara Falls. Then wrap up your trip in Idaho Falls, which is located on the Snake River.

Road Trip Highlights: Take a short detour north to visit Craters of the Moon National Park. This unique park is known for its vast, dormant lava fields and exciting hiking trails through caves.

See the very best of historic small town U.S.A. on this relaxed road trip through the Midwest. The famous Route 66, also known as the “Main Street of America,” begins in Chicago and ends at the Santa Monica Pier in California. The first chunk of the route stays in Illinois, passing charming small towns with antique shops, landmarks, and historic diners. Begin in Chicago on Lake Michigan and work your way south through Springfield, the hometown of former U.S. President Abraham Lincoln.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop in Litchfield to visit the last operating drive-in theater on the Illinois stretch of Route 66. Step back in time and enjoy a movie at Sky View Drive-In Theater for just $5 per person.

Enjoy traditional midwestern towns as you travel through Indiana from Fort Wayne to Evansville via I-69. Break up charming countryside views with Indianapolis, the largest city in the state. Check out a museum or tour the striking state capitol building. When you hit the road again, take a detour west towards Parke County and Cloverdale, which is known for its scenic covered bridges and historic farms. Continue down the interstate and end in Bloomington, a charming town in southwestern Indiana and home to Indiana University.

Road Trip Highlights: Take this drive during the fall to enjoy colorful foliage and festivals at local farms. The covered bridges and rustic barns in Parke County set the perfect backdrop for an autumn day.

Take a scenic drive on the Great River Road along the eastern border of Iowa to see the countryside from north to south. Enjoy panoramic views of the Mississippi River along your route, pulling over at protected parks and marshes along the way. For accommodations, be sure to stay in one of the many quaint bed and breakfasts. Along the Great River Road, stop at the Effigy Mounds National Monument in Harpers Ferry, the National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium in Dubuque, and the George M. Verity Riverboat Museum in Keokuk.

Road Trip Highlights: Stretch your legs at Pine Creek Grist Mill in Wildcat Den State Park. Take a relaxing stroll past waterfalls through the forest or try a hiking trail along the canyons and cliffs.

Travel along I-70, the main stretch of highway that cuts directly through Kansas from west to east, which is also known as the Prairie Trail Scenic Byway. This trip will dispel any notions of Kansas being flat and boring, and introduce you to all the spectacular scenery the state has to offer. One of the first stops through this boundless landscape is Monument Rocks National Natural Landmark. Here you’ll find unique chalk formations where 80-million-year-old fossils have been uncovered. Further east along I-70 is Mushroom Rock State Park, which is aptly named for its oddly-shaped sandstone formations.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop in Canton to take a tour of the 2,800-acre Maxwell Wildlife Refuge to view local elk, bison, birds, and native plants. The tram ride through the prairie gives guests a true taste of wild Kansas.

Take the ultimate Kentucky Bourbon Trail road trip to see the most notable distilleries in the bluegrass region. Even if you aren’t a whiskey drinker, this route also features some of the best attractions of Kentucky. Start in Louisville, Kentucky’s largest city, and home of the Kentucky Derby. Visit favorite distilleries like Angel’s Envy and Rabbit Hole, while sampling and learning the history of the trade. Continue southwest to Owensboro, a small city on the Indiana state border. Just remember, if you plan on sampling the alcohol, designate a sober driver or plan on staying the night in a nearby inn or hotel.

Road Trip Highlights: Take a tour through one of the best-selling bourbon brands in the world at Jim Beam American Stillhouse in Clermont. With a recipe dating back to the 1800s, you’ll learn the history of this successful company and sample some of their best products.

Louisiana is a melting pot of French, African, and American influences due to its creole and cajun cuisine and culture. See this in action with a scenic drive along I-10 from New Orleans to Lake Charles. Spend some time in New Orleans to start your trip with stops at Audubon Park and along Magazine Street. Continue to Lafeyette, the heart of cajun country, for some unforgettable food and local characters. At your final destination, you’ll find Lake Charles to be a lively city home to festivals, casinos, and rhythm and blues music.

Road Trip Highlights: Although each Louisiana city is enchanting, the landscapes are just as scenic. Be sure to stop along the Atchafalaya Basin, the largest marsh and bayou system in the country.

Traverse Maine’s Bold Coast Scenic Byway, a 125-mile route near the border of New Brunswick, Canada. From Milbridge, watch the rugged coastal cliffs pass by as you visit active fishing harbors and historic towns. Parts of the highway stretch inland, where you’ll experience farmland, blueberry fields, marshes, and lakes. Continue northeast until you reach Lubec, the easternmost point in the United States.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop in the charming town of Machias for delicious blueberries and a history lesson. Not only is this town known for its Wild Blueberry Festival every August, but it was also the location of the first naval battle of the American Revolution.

In an area known as “Tidewater Maryland,” you’ll find a remarkable amount of rivers, wetlands, marshes, coves, and beaches and the best way to discover them is by taking the Blue Crab Scenic Byway. Located between the Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay, this 210-mile journey links quaint, coastal villages such as Salisbury and Princess Anne for an imperfect loop. Don’t forget to try fresh-caught crab along the way.

Road Trip Highlights: See the 200-year-old neoclassical Teackle Mansion in Princess Anne and be sure to stop in Crisfield, a town famous for the Crab Derby.

Drive along the rocky New England coastline to explore Cape Ann and the charming fishing villages along the Essex Coastal Scenic Byway. Travel from Newburyport to Rockport, where you can explore art galleries, amazing seafood restaurants, and charming shops near the harbor in Rockport Cultural District. Then head south to Salem, taking in the seaside views and lighthouses dotted along the coast. It’s the perfect refreshing road trip for when you need to relax and clear your head.

Road Trip Highlights: Stop in Gloucester for a whale-watching tour to catch sight of humpback and blue whales.

Appreciate the wonder of Lake Michigan, the third largest of the five Great Lakes, from the coast of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. Starting in Grand Rapids, take Route 31 for 175 miles towards Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, where you can see massive sand dunes tower 450 feet above the waters of Lake Michigan. Expansive lake views dominate this trip as you travel north to the Straits of Mackinac — the scenic waterway between the Upper and Lower Peninsulas. On the other side of the famed Mackinac bridge are protected parks with abundant hiking, camping, and fishing.

Road Trip Highlights: If you have time, take the ferry to Mackinac Island to experience a picturesque island town completely free of cars and chain businesses.

After enjoying the cultural landmarks of Minneapolis, hop in the car and head north towards Duluth. The latter half of this journey hugs the coast of Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes. Littered with state forests and parks, mountains, and lodges, this quiet drive up holds something new around every turn. Grand Portage is the last U.S. city you’ll reach before the Canadian border.

Road Trip Highlights: Visit Split Rock Lighthouse, precariously perched on a rocky cliff. Take a tour of the historic landmark, dating back to the 1920s, or stay overnight in a cabin overlooking the lake at Split Rock Lighthouse State Park.

Spend some time in Mississippi as you traverse from capital city Jackson all the way to the Gulf Coast beaches. Highlights of Jackson include the Mississippi Freedom Trail, the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, and LeFleur’s Bluff State Park. Head south through the rural countryside and marshes, stopping along at small towns to learn more about the Civil Rights Movement and to try some delicious Southern dishes. Cruise Route 49 until Gulfport, then head over to the resort city of Biloxi on the Mississippi Sound for a little post-road-trip R&R.

Road Trip Highlights: Sometimes called the “Las Vegas of the Gulf Coast,” Biloxi is worth a visit. There, you’ll find nine casinos, along with lots of restaurants and nightlife. Additionally, Biloxi features pristine white sand beaches.

See what makes Missouri great by visiting its three largest cities — Kansas City, Springfield, and St. Louis — all in one trip. Start in Kansas City in western Missouri, which is known for its barbecue, jazz, and beautiful downtown fountains. Springfield, Missouri’s third-largest city, is less than 200 miles south of Kansas City and is a great place to visit museums and city parks. Continue northeast for 200 miles to St. Louis, home to the iconic Gateway Arch on the Mississippi River. Breweries, art museums, blues music, delicious food, and botanical gardens are just a few things to enjoy during your stay.

Road Trip Highlights: Many know of the iconic Gateway Arch in St. Louis, but few know of its detailed history. After taking pictures at the arch, stop at the Gateway Arch National Park Museum to gain a better understanding of what this arch means to St. Louis.

Enjoy the wide-open spaces of Montana and learn why the state is known as “Big Sky Country.” Start in Billings, a town full of western heritage on the Yellowstone River. Travel west on I-90, through winding roads as you transition from the Great Plains to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Once you reach Missoula, take the scenic road and travel north up Route 93 — passing through the Flathead Indian Reservation. Continuing on, you’ll find Kootenai National Forest to your west and Glacier National Park to your east. Both feature fantastic trails, campsites, and sweeping views.

Road Trip Highlights: Glacier National Park is must-see terrain on the Canadian border in Montana. Enjoy historic chalets and untouched wilderness, then travel along the famous Going-to-the-Sun Road for even more photo opportunities.

You’ll feel as if you’ve stepped back in time when exploring the Oregon National Historic Trail. Though the route passes through six states, its Nebraska leg is one of the most iconic and features several protected historic locations including California Hill and Fort Kearny State Historical Park. Explore landmarks that travelers used as they crossed the country like the Courthouse and Jail Rocks — massive clay and sandstone rock formations that jut out from the countryside. Enjoy a sunset over these unique sandstone rock formations as you make your way through the state.

Road Trip Highlights: Scotts Bluff National Monument is a must-see landmark on this road trip. This 3,000-acre park is home to remnants of the historic trail and picturesque rock formations.